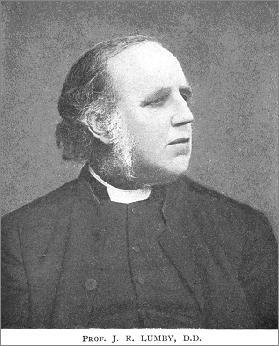

THE LIST OF honours however was at least respectable. A fair number of boys obtained scholarships, and many have since played a useful part in the life of the town. Of scholars perhaps the most distinguished were E. Atkinson, who was 3rd classic in 1842, and for over 50 years Master of Clare College, Cambridge; J. S. Wood, 4th classic, 22nd wrangler; J. R. Lumby, who besides a first class in classics won the Crosse and Tyrwhitt scholarships at Cambridge and became Norrisian professor in 1879 and Lady Margaret professor in 1892; and C. Sangster, a wrangler and winner of the chancellor's medal for English verse; for the numerous honours of C. M. Gorham, Leeds can scarcely claim the credit. The School also provided in R. Tennant another M.P. for Leeds, and at least two boys rose to high rank in the army, and one in the Indian Civil Service. It is remarkable too how many of Dr. Holmes' pupils became headmasters, though not of very famous schools.

FROM THE “GENERAL RULES,” of which every boy had to have a copy so that “he shall not be allowed to plead ignorance as an excuse for any offence,” we can get some idea as to the organization of the school in 1852. In the hours some changes had been made. In 1838 the Committee resolved that, “for the comfort of masters and scholars and convenience of families,” morning school in the winter months should be from 9 to 12, and in 1852 the hours mentioned are—

Apr. 1 to Sept. 30: 7-9: 10-12: 2-4

October and March: 8-9: 10-12: 2-4

Nov. 1 to Feb. 29: 9-12: 2-4

Wednesdays and Saturdays were still half-holidays. Lateness or absence was punished by the loss of marks. Any boy however who came to School when there was infectious disease at home was to be reported to the Committee. The School was still divided into 7 Forms, and each Form might be subdivided into “removes.” In 1852 the Upper School contained Forms vii and vi, the Middle School v and iv, the Lower School iii, ii, and i. No boy was to be put into the Middle School till he could construe and repeat all the Eton Latin Grammar and up to the defective verbs in the Greek Grammar, or into the Upper School till he could construe and repeat the whole of the Latin and Greek Grammars. In the Upper School all the boys were still taught in all subjects by the Headmaster; but in Forms iv, iii, ii, i, mathematics were taught by the writing master.

A great deal of work was still done by monitors, who supervised the learning of the lessons, were responsible for “industry, order, and compliance with the rules,” collected and distributed exercises, kept the registers of absence and lateness, and apparently added up the weekly marks. The monitors of Forms vii, v, and iii had “the general superintendence of the Upper, Middle, and Lower Schools respectively during school time,” and the highest monitor present was responsible for windows being opened at the end, and shut if necessary at the beginning, of each period. The boys were “expected to behave with attention to their monitor.”

All written work was to be neat, legible, and “correctly pointed;” impositions not done on the appointed day to be doubled; stealing, lying, swearing, indecent language, fighting, playing truant, disorder, laziness, to be punished at the discretion of the master. Boys not provided with whatever was necessary for their work or who should commit any wilful injury, or go into the Master's premises or the Library, or ring the bell, or commit indecencies in the school or schoolyard, or play, loiter, or be off the stone path on the east side of the school, or throw stones, fireworks, or fire about the school or yard, or use the Library books improperly, or be guilty of any other mischief or irregularity, were to pay a fine of 1/-. The whole School was held responsible for all damage done, and for this purpose all boys had to subscribe to a fund, into which also all fines were paid. This fund was under the charge of the head monitor, who had to see that all damages were promptly repaired and paid for. Fines not paid within a week were doubled.

AS TO THE work a few details can be gleaned.

All written exercises were done out of school, and in Greek the words had to be accented. Famous passages in English literature were often selected for translation into Greek and Latin. Stress was laid on the ability to write English, both prose and verse. English repetition was learnt from Form iv upwards, and English grammar taught in Forms i, and ii. In mathematics the standard had somewhat risen since 1820, (e.g. conics were taught), but in classics there was not much change. With every construing lesson a portion of Greek or Latin verse had to be learnt, and in construing each boy was expected to read a passage, scan it if verse, parse the words, translate, and answer questions on time, place, etc. Each Form, beginning with the lowest, came up to say its lessons “in a distinct and audible voice,” while the others were preparing work under their monitors. Every Saturday there was an examination in the Greek work done during the previous fortnight, verse and prose alternately. In divinity the syllabus was much as in 1820, but hymns were learnt by the younger boys and the 39 Articles were studied in Form vii. In the Catechism all were expected to be perfect. The Collects, Epistles, and Gospels, were learned in regular order, “in such portions as the master shall think proper.” How much time was allotted to each subject I have not been able to find out.

OF THE INDIVIDUAL masters too we now learn something.

The examiners speak highly of the work of Mr. Wilson and Mr. Ripley, but Mr. Barry thought the boys in the Middle School slack and inaccurate, nor did he like the use that was made of the cane and the “childish punishments” inflicted on lads of 15 or 16. In the “Leodiensian” there are to be found reminiscences of the infirmities—though not of the merits—of the teachers. Of Dr. Holmes himself nothing is said, but Mr. Wilson was remembered for his “habit of supplying during school a beverage composed of oatmeal and water for the comfort of thirsty pupils in the summer, and of encouraging a taste for learning by weekly prizes of coins.” Mr. Laurence is described as a strict disciplinarian and “above the mediocrity of scholastic flagellators”: his favourite implement was “a piece of slate frame.” Mr. Barry gave him credit for “steady devotion to his duties,” but doubted if he was a good enough teacher. Of Mr. Ripley we are told that he was not so hard on his pupils and that he tried to encourage boys to take pains with their writing. An ordinary punishment of his was to make a boy stand upon his seat with his coat turned inside out for a period of days or weeks. Mr. Allman, who had a room behind the main building, is credited with making boys kneel on the benches with a ledge under their knees. He had also a special punishment for liars.

“The culprit was hoisted on the back of another boy, and the Biblical account of the sin of Ananias and Sapphira was read out. Before the history of their sin was fully read Mr. Allman would make a sudden stroke at the offender with his piece of gutta-percha and hit the boy anywhere that the blow fell. The consequence was that the boy made a sudden start and jump to the amusement but not to the edification of the boys present. The history of Ananias was never finished, for Mr. Allman's way only produced noise and confusion with no salutary result.”

Mr. Barry described the writing department as “a serious evil to the school”: boys good elsewhere, he said, were bad here, and the master was unable to maintain order or to teach satisfactorily.

Those of course were Spartan days, and punishments did not err on the side of leniency. One writer speaks of being thrashed through every page of the early books of Caesar. Impositions were of daily occurrence—one cause, we are told, of the frequent complaints as to the writing. “One boy,” we hear, “wise in his generation, instead of learning his daily portion of Caesar habitually wrote it out in school hours in the form of the inevitable 'imp,' which he knew full well from past experience was sure to follow his failure in the viva voce lesson and curtail his subsequent hours of relaxation.”

And if the masters were severe upon the boys the boys were not much more merciful to one another. In early days new boys were bumped against a tree in the playground.

IN DR. HOLMES' time another custom was in vogue.

“The youngster [was] captured and laid on his back by four boys, two of whom mounted on to a table holding the struggling neophyte by the arms, whilst two others held his legs, and swinging the captive to and fro forcibly bumped him against the iron-bound edge of the table. The length of the ordeal was in direct proportion to the resistance offered and sometimes resulted in some severe bruises being inflicted, until at last, some flagrant case becoming the subject of investigation by a Select Committee of the Masters, it was finally abolished.”

Even under Mr. Barry we hear of a civil war raging between the Upper and Lower Departments, and that “a long narrow passage in the rear of the School between high walls” was the scene of many pitched battles. There were feuds also with outsiders. The boys used to attack passers-by with pea-shooters from behind the railings, and assail them with opprobrious remarks. The soldiers were more formidable victims.

“When snow lay on the ground we pelted the regiments marching down North Street . . . and the soldiers when off duty would retaliate and a fierce engagement followed. The steps of the School were lost and won amidst the cheers of the victors as the fortune of war varied, and the soldiers would roll their unfortunate prisoners in the dirty snow in the middle of North Street to the great derangement of vehicular traffic. [For many years too] a constant feud or vendetta had been waged between the Grammar School boys and the town boys. The town boys were in the habit of waylaying us in gangs as we went to and from school, and many bloody encounters ensued. We of course imitated their tactics and marched in well-ordered battalions from the school gates, dispersing in our several ways when safely through the enemy's country.” [The boys however were handicapped. A resolution, passed in 1855, ordered “that in future the boys in the School be expected to wear a College Cap, those in the higher department being distinguished by a tassel.”] “The mortar-boards revealed us wherever we went, and solitary individuals were often chivied to the very door by the enemy; it became a serious matter for us to reach the School without molestation, and many ruses and disguises had to be resorted to in order to foil the vigilance of our foes. Our mortar-boards were hid under cloaks or discarded altogether, in spite of reiterated official injunctions to the contrary.”

How long the mortar-boards remained in use I have not been able to discover. “Old boys” say that they were soon discarded. The feud however lasted longer, for even in 1884 I was told that it was not safe for boys coming from certain parts of

the town to show by any outward sign that they belonged to the School. The boys however though rough must not be regarded as bad, for Mr. Barry in his first report described the tone of the School as good, the boys as willing, and the upper boys as trying to set a good example both in industry and right-doing, and all that he complained of was “some slight defects in external discipline, and some prevalence of secret and unacknowledged mischief unworthy of the truthful honesty of a Christian school.”

_____